Thousands of U.S. troops may be living in tent cities in Liberia and supporting the fight against Ebola for “about a year” or until the deadly outbreak appears to be under control, the top military commander in Africa said Oct. 7.

“This is not a small effort and it’s not a short period of time,” Army Gen. David Rodriguez, the chief of U.S. Africa Command, told reporters at the Pentagon.

About 350 U.S. troops are now in West Africa and total deployments may reach 4,000 during the next several weeks. The size and scope of the mission has expanded from initial estimates in September, when officials said it would last about six months and require about 3,000 troops.

Pentagon officials emphasize that troops will not provide medical care or have direct contact with Ebola patients. The military mission is to support civilian health care efforts through construction of new facilities, providing logistics support and training locals in prevention methods.

Rodriguez said protocols for ensuring U.S. personnel do not contract the potentially deadly disease will include wearing gloves and masks but not complete full-body protective suits. They will wash their hands and feet multiple times a day.

And military health care team members will be taking their temperatures and asking them a series of questions every day to identify any troops who may show symptoms linked to Ebola, he said.

“We will do everything in our power to address and mitigate the potential risk to our service members. The health and safety of the team supporting this mission is our priority,” he said. “Let me assure you, by providing pre-deployment training, adhering to strict medical protocols while deployed, and carrying out carefully planned reintegration measures based on risk and exposure, I am confident that we can ensure our service members’ safety and the safety of their families and the American people.”

U.S. personnel will be housed mostly in Liberia’s Ministry of Defense facilities and in “tent cities,” and their food and water supply will be tightly controlled, Rodriguez said.

He estimated that the mission’s initial task, building 17 Ebola treatment units, each with 100 beds, will be completed by November. But many troops will remain to continue providing engineering and logistical support to the Liberians.

“We’re going to stay as long as we’re needed. … It will be about a year, but that is just a guess,” Rodriguez said.

He suggested that troops will stay until the Liberian health system is capable of finding hospital treatment beds for 70 percent of the infected population. Infectious disease experts say that’s a critical threshold for containing the outbreak.

While troops will not have direct contact with Ebola patients for now, that could change as the mission evolves. “They’ll continually relook that decision,” Rodriguez said, referring to senior U.S. officials.

If any service members contract the virus, they will be transported on an aircraft outfitted with a quarantine facility and returned to the U.S. for treatment at a top hospital, Rodriguez said. The military operation’s headquarters is not stocking the experimental drug used to treat Ebola victims, known as “ZMapp.”

The vast majority of troops deploying to Liberia will be soldiers from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and Fort Hood, Texas. In addition, at least 700 combat engineers from across the Army will be tapped for the mission. A small number of troops have deployed to an airfield in nearby Senegal and are standing by to assist if a large-scale evacuation is required.

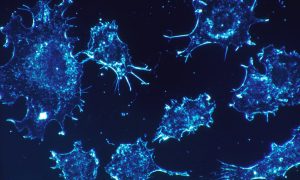

More than 3,400 people have died in West Africa form the Ebola virus and an estimated 7,470 have been diagnosed as having the infection, although the numbers likely are higher since many victims don’t make it to treatment centers.

The Defense Department effort could cost up to $1 billion, with the bulk of those funds coming from its wartime contingency budget. Congress, however, has released only $50 million in funds for Operation United Assistance, pending a complete report of operational plans and details on the use of funds.

DoD and the National Institutes of Health have been instrumental in developing potential vaccines and treatments against the deadly disease, which has a mortality rate of more than 60 percent.

This month, human safety testing will begin on a potential vaccine at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Md., and the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases began safety testing last month on a separate potential immunization.

Thomas Eric Duncan, the Liberian hospitalized at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas began receiving an experimental treatment, brincidofovir, an anti-viral drug developed by the Durham, North Carolina, based company Chimerix, that was developed to combat other potent viruses, including adenovirus and smallpox.

Chimerix has received funding from NIAID.

The FDA on Monday granted an emergency use application for an experimental treatment, brincidofovir, produced by North Carolina-based Chimerix, for use in patients with Ebola. The drug is being given reportedly to Thomas Eric Duncan, the Liberian man now fighting Ebola at a Dallas medical center.

Source: militarytimes.com

![[Video] Chicago Police Officers Caught On Video Telling Two Black Men "We Kill Mother F**kers"](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/evil-cop-3-300x180.jpg)

![[Video] Chicago Police Officers Caught On Video Telling Two Black Men "We Kill Mother F**kers"](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/evil-cop-3-80x80.jpg)

![[Video] White Woman Calls The Cops On Black Real Estate Investor, Cops Threaten To Arrest Her For Harassing Him](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/nosy-neighbor-300x180.png)

![[Video] White Woman Calls The Cops On Black Real Estate Investor, Cops Threaten To Arrest Her For Harassing Him](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/nosy-neighbor-80x80.png)

![White Scientist Says The Black Community Is Being Targeted By The Medical System, They Are Deliberatly Being Poisoned [Video]](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/mike-adams-300x180.jpg)

![White Scientist Says The Black Community Is Being Targeted By The Medical System, They Are Deliberatly Being Poisoned [Video]](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/mike-adams-80x80.jpg)

![Teenage Girl Shot In Her Stomach Three Times But Took Time To Post To Facebook [ Video]](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Gangster-chick-300x180.jpg)

![Teenage Girl Shot In Her Stomach Three Times But Took Time To Post To Facebook [ Video]](https://earhustle411.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Gangster-chick-80x80.jpg)

Pingback: The Real Truth About The Ebola Virus; Is The Red Cross Responsible? Why Are U.S Troops Really Being Sent To Africa | Ear Hustle 411